The first curious patriots arrived just after dawn and began to form a line. Standing near the low, wood-shingled, hipped roof depot of the Chicago and North Western railway, they felt the sun rising, casting its light westward onto the grass and ponderosa pine-covered Black Hills and the hogback ridge that split the city like the body of butterfly. Through a gap in that ridge, between the body and the head, the snowmelt swollen waters of Rapid Creek pressed against the burnt yellow and red rock of Cowboy Hill, before flowing through the heart of Rapid City.

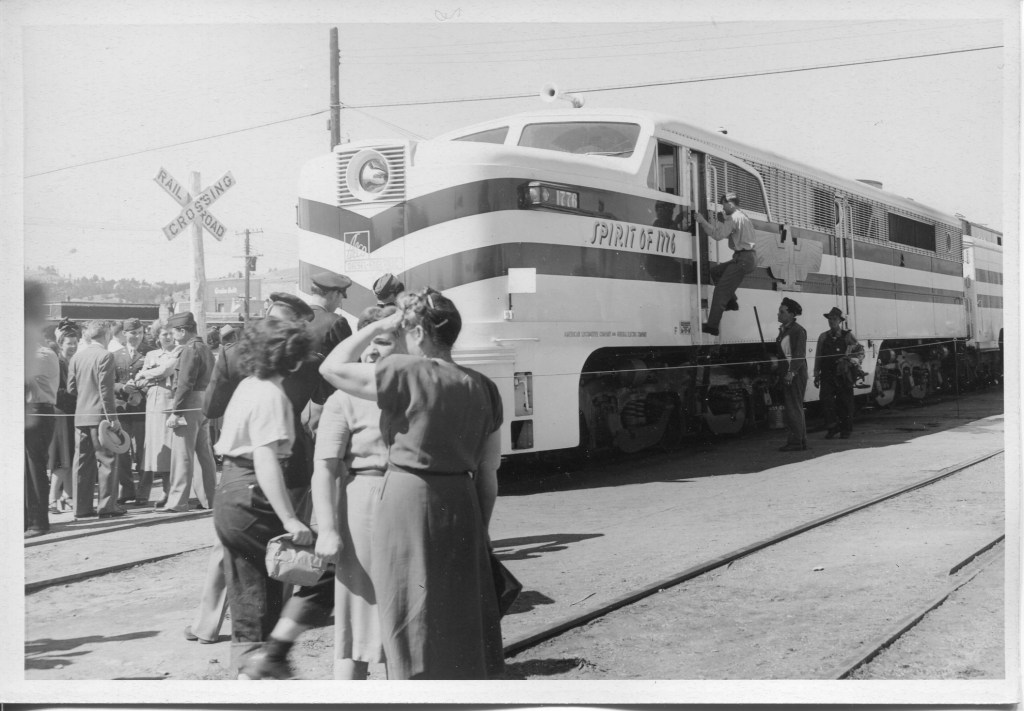

As the line grew, locals and visitors from throughout western South Dakota craned to catch a glimpse of the enormous red, white, and blue streamlined diesel-electric locomotive. Behind the “Spirit of ’76,” a series of cars, each built “like a giant safe with 20 tons of high carbon steel,” contained the sacred texts of American democracy—the Mayflower Compact, the Bill of Rights, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and George Washington’s copy of the Constitution.

By 8 a.m., the depot was jammed. A line stretched several blocks, getting longer every minute. The crowd included “all walks of life, the young, the old, the rich and poor.” Many had been anticipating this day for months. Some were school children who had been given the day off with the hope that like pilgrims restored by the bones of the saints, they would be inspired by the documents of the founding fathers. Others were veterans of two world wars who hoped their suffering would be redeemed by words that gave meaning to their shared sacrifice.

A sound system played announcements. Dressed in their red and white uniforms, with drums pounding and brass blaring, the band from Rapid City High School performed for the crowd. Boy Scouts directed traffic, while officers of the Rapid City Police Department, assisted by military police from nearby Weaver (later renamed Ellsworth) Air Force Base watched for out-of- state pickpockets and “angle boys” who traveled the country following the train hawking buttons, badges, pennants and decals as souvenirs. Some of the vendors chafed at these restrictions on free enterprise, especially when they resulted in a short stay in jail for violating some local ordinance. But the Freedom Train organizers had made it clear that they didn’t want a “carnival atmosphere” to surround the near sacred nature of the experience.

Well before the exhibits opened, 48-year old Mayor Fred Dusek arrived. A restless and energetic man who owned and operated a furniture store downtown with his wife Viola, he had lived in Rapid City since 1927. Born and raised on a farm in the sandhills of Nebraska, he had worked briefly as an accountant for the Alex Duhamel Co. before going into business. By 1948, he was a familiar figure in Rapid City government. He served as a city commissioner longer than anyone in the city’s 72-year history, before being elected mayor by his fellow commissioners in 1946.

With a strong city manager form of government, Rapid City’s mayor fulfilled mostly ceremonial duties—like presiding over the festivities surrounding the Freedom Train. But Dusek had a vision for the city and the role of government in shaping that future. It was a vision shaped by his childhood on the rural Great Plains – highly pragmatic, anchored in personal responsibility, but also committed to the collective efforts of farmers to watch out for one another and contribute to mutual prosperity.