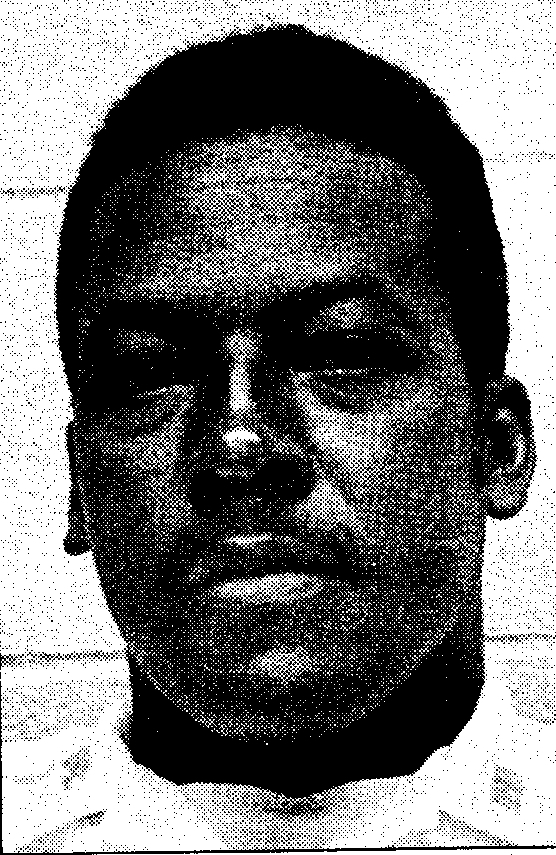

Staff Sergeant Sam Roach was more than frustrated with the elected town council of Box Elder. All he wanted was a license to sell beer, and the council refused to give it to him. With his close-cropped black hair, a thin moustache over his lip, his penetrating brown eyes, and most of all his dark skin, the muscular 37-year old Air Force veteran was sure it was because he was Black.

With nearly two decades of service in the Air Force, including wartime tours in Korea and Vietnam, Roach was one of nearly 700 African-American airmen stationed at Ellsworth Air Force Base in 1971. Many of his fellow airmen lived minutes away from the base in trailer courts and poorly built homes in Box Elder, a community of roughly 600 people living just east of Rapid City. Most of these men and their families had experienced racial prejudice since arriving at Ellsworth. If they went out to eat in some coffee shops or drink in various bars in town, they had food or drinks dumped on them by waiters or waitresses sending a message that they weren’t welcome. Plenty of landlords in Rapid City wouldn’t rent to them. To find off-base housing, they placed classified ads—“Negro airman desires 1 bedroom furnished apartment”—hoping to find one of the handful of landlords willing to take Black tenants. Many local employers—including Kmart, Woolworth’s, Gibson’s and Gambles—routinely hired the wives of White servicemen but refused to employ the wives of Black servicemen. According to Roach, most Black servicemen would rather be based in Alabama or Mississippi, than Rapid City.[1]

Over nearly three decades, African American service members stationed at Ellsworth had pushed back against this racism. The first contingent of Black servicemen arrived in the middle of World War II, shortly after the based was opened. They were part of an all-Black truck company associated with Quartermaster Corps of the US Army and commanded by three African-American officers. As reported in the nation’s largest African-American newspaper, they were the first Black soldiers to be trained “in this part of the country.”[2] Anticipating their arrival in April 1943, the Rapid City Journal ran an article touting the contributions that Black soldiers were making to the war effort.[3] Shortly thereafter, the paper noted the arrival of the “colored” Quartermaster Corps troops at the base and quoted their Black commanding officer saying the men were “right at home” in Rapid City.[4] But not all White Rapid Citians welcomed these soldiers.

Through the 1950s, successive generations of enlisted Black airmen and officers experienced discrimination when they looked for housing off base or sought services. To ameliorate the situation in 1951, the base commander and Sergeant Wendell LaFleur spoke to service clubs in town. LaFleur asked Rapid City’s White businessmen to “Look first and see a man. Then decide whether he is the type of man you’d care to associate with. Judge him as an individual, not by his color.”[5] Despite LaFleur’s appeal, business owners, landlords, and government officials continued to discriminate.

“Look first and see a man. Then decide whether he is the type of man you’d care to associate with. Judge him as an individual, not by his color.”

Sergeant Wendell LaFleur

By 1957, there were 396 Black airmen stationed at the base; 127 were married and had their families with them. Forty-six of these Black families were living off base in cabin camps in Rapid City.[6] As these airmen attended to their duties knowing that at any moment a Soviet attack could spark a nuclear war, they faced myriad challenges because of their race. One seemed simple. They lacked a decent place to go to relax and unwind.

In the mid-1950s, only two bars in Rapid City welcomed Black patrons: the Coney Island at 216 Second Street and the Plantation, located outside the city limits to the east. “Bobby” Seale, an airman who would later co-found the Black Panther Party, was stationed at Ellsworth in the 1950s. He remembered that when they had time off, “White GIs went to the white places in town. The black GIs went to the two black places.”[7] In 1957, both bars catering to Black patrons were temporarily unavailable: Coney Island because of a fire, the Plantation because it was placed off-limits by the Air Force because it lacked decent sanitary facilities. Frustrated by the situation and emboldened by increasing attention to civil rights issues nationally, Black airmen began pressing harder against discrimination.

Only three years after the US Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education, which declared segregation inherently unequal under the Constitution, and several years before lunch counter sit-ins in the American South would make headlines, a dozen Black airmen entered a downtown bar in Rapid City. When management refused to serve them, they spread out through the establishment occupying nearly a dozen booths. The men were “well-behaved,” according to a local attorney, and “while the management wouldn’t serve them, it knew it couldn’t evict them.” [8]

Black airmen also pushed for the right to open a private club that would cater to their tastes in food and music and leave them free to relax without having to worry about being taunted or abused by racist patrons or owners. Supporters of this concept enlisted Attorney Lynden Levitt who petitioned Mayor Fred Dusek and the Rapid City Common Council for a permit on behalf of the Black community. The proponents suggested various possible locations, including the old police station on Main Street.[9] The Rapid City Liquor Dealer’s Association endorsed the idea. [10] In the wake of the much publicized bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama and the integration of schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, some members of the Mayor’s recently established Committee on Human Relations resisted the establishment of Black-only club as a blatant concession to the forces of segregation.[11] But the committee did not represent the views of businessmen downtown.

In 1958, businessman John A. Oulman proposed to operate the new establishment, and he asked the Common Council to let him buy and move the Coney Island’s beer license. Eighteen downtown businesses signed a letter asking the common council to reject the application. [12] Faced with this pressure and despite the city’s repeated assurances to the Air Force that it would “do something about the problem of finding a ‘decent’ place for the Negro population from Ellsworth,” the council voted 9 to 1 to reject the license transfer, effectively killing the concept of a club for African Americans in Rapid City.[13] Meanwhile, the Coney Island continued to serve Black and Native American customers. In January 1959, some White residents of Rapid City tried to make it clear that they weren’t welcome by torching a seven-foot wooden cross wrapped in burlap and soaked in kerosene in the alley behind the establishment.[14]

Throughout the 1960s, Black airmen and their families continued to press for their civil rights in Rapid City, fighting for fair housing laws and an end to discrimination in restaurants and other public establishments. An informal survey conducted by the newspaper in 1961 found “a high degree of tolerance” for integration, but also evidence of substantial and persistent prejudice.[15] The Black Hills Civil Rights Committee, however, surveyed businesses in Rapid City and found that 90 percent of the city’s bars and barber shops still refused to serve Black customers, along with 30 percent of the restaurants and motels. “The problem is acute … in this city in the shadow of the ‘Shrine of Democracy,” reported the New York Times.[16]

For many Black airman, the lack of a safe place to go to relax continued to be a problem. In 1961, the city barred the Coney Island from selling alcohol. In response, the owners, George and Adella Hudson, opened George’s Jazz Cellar in the basement, but the city quickly shut it down.[17] Asserting that they were being unfairly targeted by the city because they were Black and catered to a Black clientele, the Hudson’s hired attorney Ramon Roubideaux to defend them. In court, Roubideaux’s entire defense focused on the city’s failure to provide public accommodations to Black airmen and their families. He reiterated the point, “All these people want is the right to be left alone and they’re entitled to that.”[18]

Meanwhile, Hudson made plans to open a restaurant on property the Hudson’s owned at the corner of Maple and Madison Streets in North Rapid City.[19] Segregationists asked the council to stop the project. Some ignited a ten-foot flaming cross on the property. Hudson chased them away by firing a shotgun into the air.[20] The city’s mayor personally offered a reward for information that would lead to the arrest of the perpetrators. “It is time the responsible element in this city got on the ball and end the acts inspired by irresponsible radicals,” the mayor said.[21]

Worried that cross-burnings and other flagrant acts of racism would tarnish the city’s image, the mayor pushed local businessmen to support the opening of Hudson’s restaurant. After Hudson’s place opened, one segregationist pointed to the establishment as proof that the Common Council and business leaders had the best interests of Black airmen in mind. “Now they’ve got a beautiful place of their own where they can go,” explained one White restaurant owner. “We felt that we wanted to give them something. This town has bent over more than backward for them. The only thing we’re scared of is the young ones coming in and trying to intermingle.”[22] The stress of fighting the city’s segregationists, however, proved too much for Hudson. In January, 1963, the 39-year old Paris, Texas native died.[23]

With Hudson’s death, Black airmen’s hopes of having a place of their own were once again put on hold. Meanwhile, the South Dakota Advisory Committee of the United States Commission on Civil Rights launched an investigation into race relations in Rapid City in the early 1960s.[24] Shortly after the Commission completed its work, the South Dakota Legislature passed a law prohibiting racial discrimination in public accommodations, but discrimination in Rapid City continued.[25] In 1969, the Rapid City Journal ran a series of stories profiling the “City’s Black Man Alone, Unhappy.” Despite significant advances in civil rights around the country and the rise of the Black Power movement, airmen continued to face prejudice even though the South Dakota Governor Frank Farrar insisted, “there’s no discrimination in South Dakota.”[26]

Sam Roach knew the governor’s statement was a lie. When the city of Box Elder refused to grant him a license to sell 3.2 percent beer, he recruited a White friend to submit an application instead, but when local officials discovered the subterfuge, Roach’s friend caught “holy hell from the town council.”[27] Frustrated by what he thought were obvious acts of discrimination, Roach called on his fellow African-American airmen to protest.

In a letter to the editor of the Rapid City Journal in March 1971, headlined “Black man’s complaint,” he noted that there were approximately 700 Black servicemen stationed at Ellsworth, but Rapid City and the nearby community of Box Elder had “refused to accept the black man into the community.” Most landlords refused to rent to African Americans. Those that did, leveled a surcharge. When Black entrepreneurs sought to open their own establishments, White city officials refused to issue them a license to sell alcohol. Roach urged his fellow Black airmen to write to their congressmen and to the President and “that the USAF either refrain from shipping blacks to Ellsworth, close the base, or place the town off limits to all military personnel.”[28]

Roach may have been emboldened to launch his protest because he knew he was leaving the Air Force. Unable to start a bar in Box Elder, he joined the Rapid City Police Department as a patrolman instead. But Roach did not give up on his dream of opening a bar or nightclub where Black servicemen could relax without fear of racism. In the summer of 1971, he began talking to Mary Long, who owned and managed the Stirrup Lounge & Café at 728 Main Street.[29]

The Stirrup was located among a series of bars in downtown Rapid City. The district was a constant source of trouble for the Rapid City Police Department and a headache for local officials who received frequent complaints from citizens, including former Mayor Fred Dusek. Some members of the council along with leaders at the Rapid City Chamber of Commerce were pushing the city to secure federal urban renewal funds to tear down the entire block. Earlier in the year, the city had suspended the Stirrup’s license to sell beer and wine because of several liquor violations and issues with disturbing the peace. Long pleaded with the council, noting that her husband was sick, and promising that she would either run the place herself or find a good manager. Instead, she decided to sell the place to Roach.[30]

When he took over the Stirrup that fall, Roach faced a number of challenges, including various code violations that had to be fixed. Sam pressed the landlord to make these improvements. When the landlord failed to act, Sam withheld rent payments and paid for some of the work himself. In January, a customer pulled a gun and Sam threw him through a glass window.[31]

Despite all of these difficulties, Roach was able to transform the Stirrup into Sam’s Ebony Club, featuring “Soul Music — Soul Food” and “Go-Go Girls.”[32] The Club catered to the late night crowd. Entertainers started their sets at 10:00 pm and played until 2:00 in the morning with the smells of cigarette smoke, grease and beer permeating the air.[33] After closing and cleaning up, Sam went upstairs to sleep in his apartment as Rapid City stirred to life and the sun began to rise in the east.[34]

Trouble started almost as soon as the Ebony Club opened. After midnight on Friday, January 21, Roach was trying to eject a 16-year old youth who had come into the bar. A number of customers began arguing with him. One was a 24-year old airman who opened his coat to reveal an automatic pistol in a shoulder holster. Fearing for his safety, Roach pulled out his own .22 caliber revolver and fired, injuring the airman.

As the struggle continued, the 16-year old grabbed the airman’s gun and bolted out the door with Roach in pursuit. Out on the sidewalk, the youth turned and fired at Roach, but missed. Meanwhile, an angry crowd grabbed Roach and pinned him to the ground.

After the police calmed everyone down, the airman was taken away in an ambulance while officers searched for the youth. Half an hour later, the bar was on fire. Fire department officials discovered that gasoline and other inflammables had been poured on the back door to the alley and ignited. The Fire Department responded and extinguished the blaze, but not before it caused hundreds of dollars of damage and someone lifted approximately $185 from the cash register.[35]

Despite the “ruckus,” reported by the paper, Roach was back in business the next week, but once again the Ebony Club ran into trouble with law enforcement. Long after midnight on January 29, the police responded to three disturbance calls and ultimately closed the bar and arrested two women. As the Ebony Club’s uneasy relationship with the police department and city officials continued over the next month, the realtor who owned the property decided to evict Sam and his business at the end of February.

Sam’s 20-year old White girl friend was incensed. Donna Ethel Frenzen had grown up in Rapid City and attended Central High School. Married and divorced already, she was dating Sam in the fall of 1971 when he was planning to take over the Stirrup and was shocked by the treatment she received when she began appearing with a Black man in public. There were anonymous obscene phone calls. Her employer fired her after 14 months. Her landlord evicted her because they didn’t want a Black man in the house. In protest, Donna wrote a letter to the editor to ask why federal laws barring discrimination weren’t being enforced.[36]

Donna continued to be an advocate after the Ebony Club was evicted from the location on Main Street. In another letter to the editor titled “Our one black bar,” she chastised Rapid City’s “so-called American businessmen” for targeting a Black business owner. If fights were the issue, she said, “every bar on Main Street should be closed.”[37]

Meanwhile, Sam began looking for a new location for the Ebony Club. He rented space on East North Street and petitioned the city to let him move the club’s beer license. Then he discovered that the adjacent business owners bought the property so that they could prevent him from moving in.[38]

Donna was not about to let city bureaucrats hide what she saw as blatant discrimination. She began organizing a protest march and hoped to enlist the hundreds of Black airmen at the base. On April 4, she appeared before Mayor Don Barnett and the common council to call them out for being unfair, to chastise business leaders for discriminating, and then castigate the entire community for prejudice against Blacks and unwillingness to provide African Americans with “a place of their own.” She accused the Air Force of assigning Black men to Ellsworth “against their will and without their consent.” To put pressure on the city, she said she had written “to high officials from the President on down and asked the Air Force to declare the city off limits to airmen.”[39]

Mayor Barnett rejected Donna’s criticisms of the council and the community. He also made it clear that if she submitted the proper application for a parade, he would make sure that it was processed. [40] Three days later, Donna was able to organize 75 men and women to walk down Sixth Street carrying signs protesting the closure of the Ebony and insisting “We Want Our Own Bar Now.” But the Ebony did not reopen.

Whether Sam Roach was in the room on the night that Donna blasted the common council is not clear, but it seems likely that he had already given up on the Ebony Club and knew he needed to go back to work. That night, as the Common Council continued on their agenda, they approved a plan to hire three new patrolmen for the Rapid City Police Department. One of them was Sam Roach.

[1] “Black man’s complaint,” Rapid City Journal, March 3, 1971, 5.

[2] “Truck Company Officers in S. Dakota First Time,” New York Amsterdam News, May 29, 1943, 11.

[3] “American Negro Now Doing a Major Part,” Rapid City Journal, April 6, 1943, 4.

[4] “First Colored Troops Arrive at Local Base,” Rapid City Journal, April 13, 1943, 4. See also, “Negro Sergeant Was In World War One,” Rapid City Journal, April 20, 1943, 7.

[5] “Mutual Problems of City and Air Base Reviewed,” Rapid City Journal, December 17, 1951, 3.

[6] These figures were offered by Attorney Lynden Levitt in a hearing before the Rapid City Common Council. “Council Delays Action on Beer License Move,” Rapid City Journal, February 18, 1958, 3.

[7] Stephen Shames and Bobby Seale, Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers (New York, Abrams Books, 2016).

[8] Ken Jumper, “Club License Sought to Care for Negroes,” Rapid City Journal, March 19, 1957, 2.

[9] Ken Jumper, “Club License Sought to Care for Negroes,” Rapid City Journal, March 19, 1957, 2.

[10] Ken Jumper, “Club License Sought to Care for Negroes,” Rapid City Journal, March 19, 1957, 2.

[11] “Mayor’s Committee Talks Indian Housing and Negro Segregation,” Rapid City Journal, March 23, 1957, 13.

[12] Ken Jumper, “Club License Sought to Care for Negroes,” Rapid City Journal, March 19, 1957, 2. See also, “Suggestions Heard, No Action On Main Street Beer Bar License Request,” Rapid City Journal, February 25, 1958, 3.

[13] “Transfer of License is Rejected,” Rapid City Journal, March 4, 1958, 3.

[14] “Klan Theory Discounted in Cross Burning,” Rapid City Journal, January 30, 1959, 1.

[15] Pat McCarty, “High Degree of Tolerance Found Toward Negroes,” Rapid City Journal, February 5, 1961, 3.

[16] Donald Janson, “South Dakota Northern Pocket of Discrimination,” New York Times, October 22, 1962, 18

[17] “Jazz Cellar Case Begins Wednesday,” Rapid City Journal, June 21, 1961, 3.

[18] “Restraining Order Issued on Coney Island Property,” Rapid City Journal, March 8, 1962, 3.

[19] “Restaurant, Parking Meter Issues Come to Council,” Rapid City Journal, August 8, 1961, 3.

[20] “Police probe cross burning Friday night,” Rapid City Journal, August 12, 1961, 3.

[21] “100 Reward Offered For Arrest of Cross Burners,” Rapid City Journal, August 13, 1961, 3.

[22] Donald Janson, “South Dakota Northern Pocket of Discrimination,” New York Times, October 22, 1962, 18

[23] “George Hudson Dies Saturday in Hospital,” Rapid City Journal, January 12, 1963, 3.

[24] South Dakota Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights “Report on Rapid City” (March 1963): 45–47.

[25] Vanepps-Taylor, Forgotten Lives, 186–188. Joseph T. Boone, “For Fair Housing,” Rapid City Journal, February 22, 1967. Ed Martley, “Hearing Continued on Public Accommodations Law Complaint,” Rapid City Journal, October 26, 1968.

[26] Bill Wagner, “City’s Black Man Alone, Unhappy,” Rapid City Journal, November 2, 1969, 1.

[27] “Black man’s complaint,” Rapid City Journal, March 3, 1971, 5. See also, Box Elder Board of Trustees, Minutes, November 10, 1970, Rapid City Journal, December 1, 1970, 17.

[28] “Black man’s complaint,” Rapid City Journal, March 3, 1971, 5.

[29] Display ad, Rapid City Journal, November 25, 1970, 11. The City Council considered the transfer of beer licenses from Lawrence Wardrope to Mary J. Long for this establishment on February 11, 1971. Bob Fell, “Committee questions rural fire costs, transfers of two city beer licenses,” Rapid City Journal, February 11, 1971, 3. This transfer approval was delayed over subsequent meetings pending information from the Sheriff’s Department. Apparently Long’s husband Frank had operated the Old Town south of the city. Also, Long planned to hire James L. Bush as manager, but Bush had been convicted of several liquor violations.

[30] Rapid City Common Council, “Official Proceedings,” August 2, 1971, in Rapid City Journal, August 7, 1971, 10.

[31] “Council asked to approve black parade on Friday,” Rapid City Journal, April 4, 1972, 4.

[32] “Grand Opening” advertisement, Rapid City Journal, January 5, 1972, 8, and “Ebony Club” advertisement, Rapid City Journal, January 15, 1972, 4.

[33] “Grand Opening,” Rapid City Journal, January 5, 1972, 8.

[34] “Shooting, arson theft involved in bar ruckus,” Rapid City Journal, January 21, 1972, 3.

[35] “Shooting, arson theft involved in bar ruckus,” Rapid City Journal, January 21, 1972, 3.

[36] Donna E. Simpson, “Discrimination,” Rapid City Journal, November 3, 1971, 11.

[37] Donna E. Simpson, “Our one black bar,” Rapid City Journal, March 21, 1972, 5.

[38] “Panel to study 40 applications for liquor permit,” Rapid City Journal, March 29, 1972, 2.

[39] “Council asked to approve black parade on Friday,” Rapid City Journal, April 4, 1972, 3.

[40] “Council asked to approve black parade on Friday,” Rapid City Journal, April 4, 1972, 3.